If you’re on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook, you’ve probably seen #RepresentationMatters floating around. The phrase checks all the boxes for social media – it’s trendy, catchy, and well-suited to describe an expansive list of fields and situations.

But what is representation when it comes to politics? Who are our representatives, how do we choose them, and what roles can and should they fill beyond being legislators? Why does representation matter? What are the limitations of representation and how can we gauge the success of a representative? And how do current political, societal, and economic situations necessitate enhanced political representation?

Recent events and a looming national election have brought representation – particularly gender representation – to the forefront of political discourse again. 2020 has proven to be historic in numerous ways; but, for meaningful insight into political representation, the outcomes of the 2018 midterm election still yield countless important lessons. As we approach November with an eye towards gender and intersectionality in American politics, it’s worth understanding what political representation is and it’s worth considering what we can learn from the past.

Demystifying Political Representation

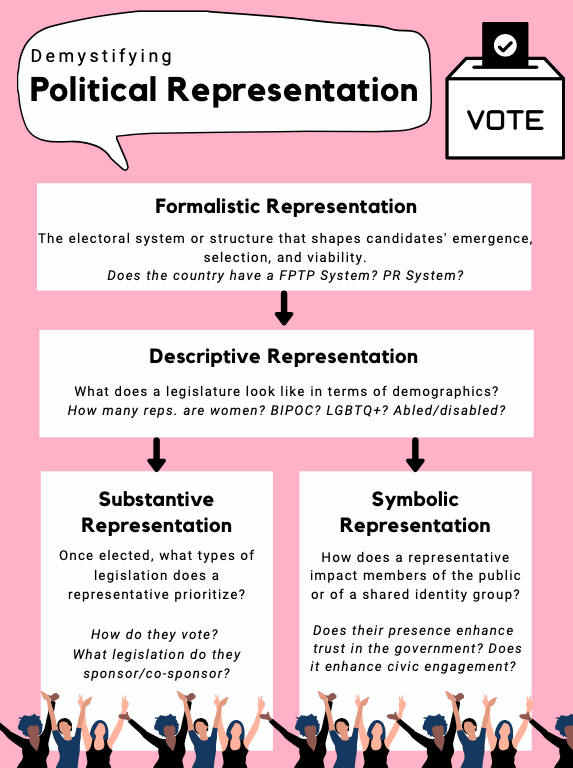

Political representation is a concept used in political science scholarship, and it can be distilled into four primary components: formalistic, descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation. Each is defined by Hannah Pitkin in her 1967 book, The Concept of Representation. In short, political representation refers to the presence of different identity groups in politics, the impacts these groups have, and structures that affect the likelihood that such groups will break into the political sphere.

Formalistic representation denotes the formal institutions and systems that determine the structure of elections and affect how candidates emerge and are selected. The United States employs a “First Past the Post” (FPTP) electoral system. This means that the candidate who receives the most votes in a given election is the candidate who wins – in other words, the winner takes all. Other countries may use proportional representation (PR) systems, where the composition of seats in multi-member districts is proportional to the number of votes received by different parties.

Descriptive representation refers to the demographic composition of legislatures, or who is present. Do representatives look like the constituents they serve? Let’s look at the current makeup of the U.S. Congress. According to the Center for American Women and Politics, of the 535 members serving, women are 23.7%. Of these women, 37.8% are women of color. Of all members of Congress, 9% are women of color. Descriptive representation isn’t limited to race and gender; it can refer to nearly any identity, including religion, sexuality, age, or ability.

Substantive representation considers the actual actions of elected officials. What pieces of legislation has a representative sponsored or co-sponsored? How does a representative vote on different issues? Are these actions reflective of the interests of constituents?

Symbolic representation refers to the emotional response that a representative’s presence elicits. The presence of a representative belonging to a historically marginalized group, for example, may have a variety of effects on those being represented. Some individuals may be more inspired to run for office or envision themselves in a position of leadership. Others may feel a greater sense of trust in political institutions or become more civically engaged.

Why Representation Matters

In the historic 2018 midterm – an election that was viewed as a referendum on Donald Trump’s 2016 victory – a record number of women belonging to different visible and invisible identity groups were elected to the U.S. Congress. Though Congress remains disproportionately white and male, the shifting demographics of the institution after the 2018 midterm in terms of gender, race, sexuality, age, religion, ability, and members’ professional and personal backgrounds exemplify descriptive representation.

Deb Haaland is one of these women. When Haaland (D-NM) was elected to represent New Mexico’s First Congressional District in 2018, she joined Sharice Davids (D-KS) in becoming one of the first Native American women to serve in Congress. When campaigning for the office she now holds, one of the issues Haaland prioritized was gender equality. However, unlike many of her colleagues, the lens through which Haaland viewed gender equality highlighted the unique injustices and forms of violence that Native American women face.

Since being sworn into the 116th U.S. Congress, Haaland has shown that violence against Native American women remains a priority of hers. In July of 2019, Haaland introduced H.R.3977, the Justice for Native Survivors of Sexual Violence Act. In November of 2019, Haaland introduced a resolution, H.Res.735 “recognizing the maternal health crisis among indigenous women in the United States.” Now, as Haaland campaigns for re-election in 2020, she hasn’t given up this fight.

Haaland’s presence in the legislative branch has been symbolic in various ways. As a representative, Haaland has given other Native American individuals and tribal leaders the opportunity to speak before her colleagues. In many ways, this gesture signifies that these communities now have an ally who will ensure that their voices are amplified. For another example, consider the date that Haaland was sworn; Haaland wore a traditional Pueblo dress and customary Native American jewelry, and was joined by her family, who also wore traditional clothing. In this moment, she became the first elected member of Congress to do so in the Capitol Building during a swearing-in ceremony.

The structure of our electoral system- in conjunction with other systems of oppression- are responsible for the fact that it took until 2018 to elect Native American women to Congress. With their election came a renewed focus on considering legislation through a lens that is inclusive of marginalized communities. Moreover, the symbolic implications of having historically underrepresented groups present in the halls of Congress cannot be overstated and will have far-reaching impacts on our democracy.

What About Other Newly Elected Members?

Haaland wasn’t the only woman who broke barriers in 2018 while also bringing her personal experiences and identities to Congress. Lucy McBath (D-GA) was elected in 2018, 6 years after her son Jordan was shot and killed. After focusing much of her energy as a candidate on gun violence prevention, McBath introduced H.R.3076 in 2019 to effectuate common-sense gun violence prevention. Lauren Underwood (D-IL) was elected as the youngest black woman in the history of the U.S. Congress after serving as a nurse and health policy expert. In the time that she’s served in Congress, Underwood has introduced bills including H.R.6142, which pertains to black maternal health, and H.R.5444, which concerns lowering the prices of insulin.

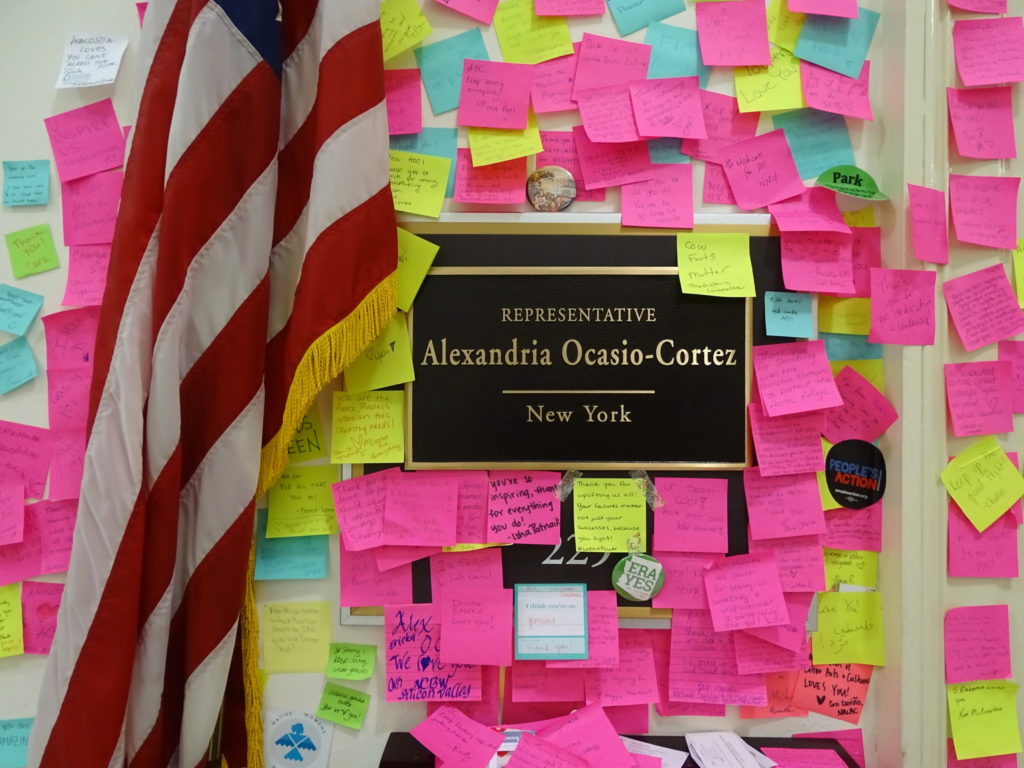

It couldn’t be clearer that newly elected women have also had symbolic impacts on those they serve. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) became the youngest woman elected to Congress when she won in 2018. Since then, she has made it a point to speak directly to other young people. After her victory, Ocasio-Cortez encouraged young people to participate in politics and run for office, stating, “Congress is supposed to represent the American people. One of the largest electorates right now are millennials and young people … Frankly, if we’re not in the halls of Congress, then Congress isn’t working.”

Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), another newly elected progressive, revealed in early 2020 that she has alopecia, an autoimmune disease that causes hair loss. Recognizing her powerful platform and responsibility to serve as a role model, Pressley opened up about this health condition, stating, “I hope this starts a conversation about the personal struggles we navigate, and I hope that it creates awareness about how many people are impacted by alopecia.”

We live in a representative democracy. As such, it is antithetical to founding democratic principles to have a government that doesn’t look like the people it serves. Enhancing the representation of not only women, but women of different races, religions, sexualities, ages, and abilities allows the American people to see themselves in politics. If seeing is believing, the importance of representation cannot be overstated.

A Note on Representation

It’s worth noting that representation has limitations. Of course, any one representative is still just one person. This means that they are limited to their singular experiences and perspectives, which may in turn inform their roles and values as legislators. For example, electing a white woman belonging to the middle class does not mean that all women will have a voice in Washington.

It should also go without saying that all representatives should care about issues disproportionately affecting certain communities – such as Native American communities – and that in their capacities as elected officials, all representatives have the ability to support and introduce legislation to assist such communities. Unfortunately, too often representatives are unlikely to recognize the severity or existence of those issues that do not uniquely and directly affect their health, security, or wellbeing.

As Haaland has said, on the topic of issues disproportionately impacting Native American communities: “If I weren’t here, if Sharice weren’t here, who would be thinking about those things?”

Beyond the Halls of Congress

The impacts of political representation can be felt far beyond the halls of Congress. In many ways, the policies shaped by state and local political offices affect the lives, security, and wellbeing of communities more immediately and more tangibly than those introduced in Congress. Though state and local elections generate less attention than national elections do, electing candidates with diverse identities, experiences, and perspectives similarly has the potential to enhance discourse and civic engagement while also inspiring policies that are more responsive to and representative of constituents’ needs.

Consider the impact that Ella Jones had when she was elected the first Black and first woman mayor of Ferguson, Missouri in June of 2020. Ferguson garnered national attention in 2014 when Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, was shot and killed by the police. This sparked a series of protests that spotlighted the Black Lives Matter movement. Jones campaigned on issues including public safety, youth engagement, and community engagement, and since winning her mayoral election has said, “My election gives people hope. Everybody is looking for a change, everybody wants a better way of life … I have been living in injustice my whole life.”

How about Rosemary Ketchum? Ketchum, a community organizer and activist, made history in early June by becoming the first openly transgender individual elected in West Virginia when she was elected to the Wheeling City Council. After her victory, Ketchum told reporters that she “(feels) excited to represent inclusivity.” In response to Ketchum’s achievement, the LGBTQ Victory Fund, a political action committee, said in a statement that “Rosemary’s victory will resonate well beyond her state” and “will inspire other trans people … to consider a run for office in their communities.”

What’s at Stake in 2020?

Like 2018, the 2020 election is shaping up to be historic in numerous ways. According to the Center for American Women and Politics, 60 women have filed to run for U.S. Senate seats, which exceeds the record 53 women who filed to run for these seats in 2018. 584 women have filed to run for seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, exceeding the record of 476 set in 2018.

These women candidates come from different backgrounds and belong to different identity groups. In New Mexico, it is possible that an all-female delegation will be elected to the House of Representatives in the fall. More notably, various sources anticipate that this delegation will be entirely composed of women of color. According to EMILY’s List, multiple women of color are running to flip congressional seats in states ranging from New York to Texas. Women belonging to the LGBTQ+ community are running, as are women with professional backgrounds in education, public service, healthcare, and military service, among others.

Unlike 2018, however, these candidates are running against a social, political, and economic backdrop that is almost unparalleled. Grappling with a pandemic and facing renewed national discussions about the realities of systemic racism and oppression amid the George Floyd protests, this year has thrown unprecedented challenges at underrepresented communities. Many of these crises are interrelated, and many of these challenges disproportionately impact women and women of color.

If scientists develop an effective vaccination for COVID-19 and the public protests surrounding police brutality and systemic oppression begin to fade, public health, domestic violence, income inequality, and racism will still exist and will still disproportionately impact marginalized communities. Current events have shed light on why electing diverse women candidates matters now more than ever.

What Can Be Done in the Meantime?

Support women running for office. Support women of color. Support women who will bring their rich experiences and perspectives to Congress and their local communities, from their professional backgrounds to their visible and invisible identities.

Some women are running to flip congressional districts this fall. Get familiar with these names: Jackie Gordon, a veteran, educator, and community leader, is running to flip New York’s Second Congressional District. Pat Timmons-Goodson, who serves on the United States Commission on Civil Rights, is running to flip North Carolina’s Eighth Congressional District. Candace Valenzuela, who struggled with homelessness before becoming a first-generation college graduate and an at-large representative on the Carrollton-Farmers Branch Independent School District board, is running to flip Texas’ 24th Congressional District.

Other women – including those mentioned earlier – are running to keep the seats they won in 2018 or earlier. Incumbent women in Congress need your support too. Beyond the halls of Congress, it is critical to support women running for state and local offices. Women running for these offices face barriers much like those that women running for Congress face; as such, every penny donated and every minute spent volunteering has the potential to carry these candidates to victory in state and local elections.

There are different ways to support candidates, even during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consider making phone calls or sending text messages on behalf of candidates; donating to campaigns or organizations that support women running for office; encouraging others to donate; registering to vote; and making sure your friends and family are registered to vote.

It’s on us to enhance representation in politics. This means electing more women, but also electing diverse women. Identity politics is real, it matters, and we’ve been watching it play out for years. Politicians’ unique experiences and perspectives inform their values and priorities. It’s time that these values and priorities align with those held by the American people.